INTRODUCTION

The early successes of the Civil Rights Movement were mostly the work of courageous individuals. Presidents, business leaders, judges, and eventually students bravely chose justice over prejudice and made decisions that were unpopular, and sometimes even dangerous. The days of the great marches led by inspirational leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. were still to come.

What made these individuals do what they did? Why did they decide to risk their lives, or public support to make change happen? Why did they look at the wrongs of the world and decide that it was up to them to make change?

And, how was it that individual Americans, sometimes only children, helped overcome generations of established law and discrimination? What special abilities, talents, or powers made their efforts successful?

How did individuals advance the Civil Rights Movement?

A LONG STRUGGLE FOR JUSTICE

The Civil Rights Movement of marches, boycotts, and great speeches by leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr that many Americans are at least passingly familiar with did not suddenly emerge from thin air. In fact, African Americans had been working for racial justice for many years.

As amazing as it may seem, slavery existed in the United States, or the land that became the United States, for longer than it has not. The first slaves were brought to the Virginia Colony in 1619 and slavery was not legally ended by the 13th Amendment until after the Civil War in 1865. That’s a total of 246 years. It has been just over a century and a half since the end of the Civil War, which means, slavery existed for 100 years more in our nation than it has not, and it would be wrong to think that the subjugation of millions of people because of their skin color did not leave a lasting mark on our nation.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, three amendments to the Constitution were ratified, ending slavery, grating citizenship to Americans of all races, and granting voting rights to all men. Together, these three radical changes to America’s social order and democratic norms could have formed the basis for an entirely new way of life in the South. However, after years of war, and another ten years of occupation of the defeated South, Northerners grew tired of the project of Reconstruction and in 1877 the armies of the North returned home and abandoned their project of creating a new, more racially integrated South. In their absence, White leaders reclaimed power and established a system of regulations, both through law and tradition, which reestablished White authority.

The social order of the Old South returned. African Americans were relegated to the bottom rung of society. They lived in the worst neighborhoods and had the worst jobs, or lived as tenant farmers stuck permanently on land where they always owed rent to White landlords. Across the land, African Americans and Whites dined at separate restaurants, bathed in separate swimming pools, drank from separate water fountains and went to different schools. African Americans could not vote, could not run for office, and could not change their position in life. The degradation of African Americans was complete. It pervaded jobs, schools, government and even language itself. Whites were accustomed to calling all African American men “boy” regardless of age. This new system became known as Jim Crow.

At first, prominent African American leaders sought to improve the lives of their people through education. Booker T. Washington, for example opened the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, but he was fearful that fighting openly for equality would lead to violence and more oppression.

It was not until the 1900s that African American leaders began openly calling for equal rights. Among the most prominent was W. E. B. Du Bois and the other leaders of the Niagara Movement. In the 1920s, the Great Migration brought thousands of African Americans to the cities of the North and through the work of Du Bois and great writers like Langston Hughes, the Harlem Renaissance led to the emergence of the idea of the New Negro, and the real struggle for equality was born. Importantly, along with a new sense of pride and mission, African American leaders at the start of the 1900s also created the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to fight for their rights in the courts.

During World War II, another important leader campaigned for equality. A. Philip Randolph, the leader of the union of railroad porters successfully convinced President Franklin Roosevelt to outlaw discrimination in businesses that did work for the federal government.

Despite these gains, however, much work remained undone. Primary Source: Newspaper

Primary Source: Newspaper

President Truman’s Executive Order 9981 was an important step toward integration in the country and was undertaken in his role as Commander in Chief of the armed forces. Because of the president’s power in this capacity, he did not need to win approval or public support before making the change.

CIVIL RIGHTS IN THE AFTERMATH OF WORLD WAR II

In the aftermath of World War II, America sought to demonstrate to the world the merit of free democracies over communist dictatorships. But its segregation system exposed fundamental hypocrisy. How could the nation argue that it represented freedom when millions of its own citizens were denied basic rights? In fact, the leaders of the Soviet Union and communist China were eager to point out American hypocrisy whenever American politicians accused them of human rights violations.

One of the first changes to take place came from the world of sports. In 1947, the owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers baseball team decided to put Jackie Robinson on the field and broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier. Until then, the many talented African American baseball players had to play in their own leagues, the Negro Leagues, a mirror of the all-White major leagues. As African American fans flocked to see the Dodgers play, other owners followed suit and integrated their own teams.

Another bold move in the early post-war era, was the full integration of the armed forces. In 1948, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981 bringing about the end of segregation in the armed services. No longer would there be Whites-Only or Blacks-Only units in the army or other branches of the service. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

Emmitt Till was only a boy when he was killed for violating the racist traditions of the South. His murder brought attention to the Jim Crow system that was maintained with the threat of violence.

But the orderly rules of the baseball field and the formal structures of the military were relatively easy to integrate compared to the complexity of everyday life, especially in the deeply segregated South. And no event illustrated just how dangerous the struggle would be more so than the murder of Emmitt Till. Till was born and raised in Chicago and he understood racism, but Emmitt did not grow up learning the strict racial codes of the Jim Crow South. During summer vacation in August 1955, while visiting relatives in Mississippi, he spoke to 21-year-old Carolyn Bryant, the White married proprietor of a small grocery store. Although what happened at the store is a matter of dispute, Whites in the area believed Till had been flirting with or whistling at Bryant. Several nights after the store incident, Bryant’s husband and his half-brother went armed to Till’s great-uncle’s house and abducted the boy. They took him away and beat and mutilated him before shooting him in the head and sinking his body in the Tallahatchie River.

Three days later, Till’s body was discovered and returned to Chicago where his mother insisted on a public funeral service with an open casket so the world would know what had been done to her son. Photographs of Till’s bloated, mutilated body were published in magazines and newspapers, rallying support and sympathy across the country and focusing a light on the racism and violence of the South. The men who murdered Till were acquitted by an all-White jury. The entire episode, from the Jim Crow system that condoned segregation and racial hatred, to the murder and trial showed the extent to which White power was rooted in the society of the South and perpetuated with violence and fear.

BROWN v. BOARD OF EDUCATION

One of the first areas of success for Civil Rights activists was in the courts. In 1896, the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision declared that segregated schools were legal, so long as they were equal.

In no state where distinct racial education laws existed was there equality in public spending. Teachers in White schools were paid better wages, school buildings for White students were maintained more carefully, and funds for educational materials flowed more liberally into White schools. States normally spent 10 to 20 times on the education of White students as they spent on African American students.

In the 1950s, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), led by attorney Thurgood Marshall, sued public schools across the South, insisting that the “separate but equal” clause of the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling had been violated.

The Supreme Court finally decided to rule on this subject in 1954 in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka case. The verdict was unanimous against segregation. “Separate facilities are inherently unequal,” wrote Chief Justice Earl Warren. Warren worked tirelessly to achieve a 9-0 ruling. He feared any dissent might provide a legal argument for the forces against integration. The united Supreme Court sent a clear message: schools had to integrate.

School leaders in the North complied with the ruling, but the Brown decision was received angrily by Whites in the South. The Court had stopped short of insisting on immediate integration, instead asking local governments to comply “with all deliberate speed.” Ten years after Brown, fewer than 10% of southern public schools had integrated. Some areas achieved a 0% compliance rate. Rather than opening their schools to African Americans, many White leaders simply closed their schools entirely. In one county in Virginia, for example, the White county government simply stopped appropriating money for schools. Instead, they provided funding for students to attend private schools. Then, they closed the public schools and reopened them as private schools that admitted only White students.

So, despite the ruling by the Supreme Court, it took the work of many brave Americans to make integrated schools a reality. Primary Source: Photographs

Primary Source: Photographs

Many White Southerners were angered by the Brown v. Board of Education decision of the Supreme Court.

THE LITTLE ROCK NINE

Three years after the Supreme Court declared race-based segregation illegal, a showdown took place in Little Rock, Arkansas. On September 3, 1957, nine African American students attempted to attend the all-White Central High School. When it was clear that White mobs were likely to violently stop the students, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus mobilized the Arkansas National Guard to prevent the students, known as the Little Rock Nine, from entering the school. After a federal judge declared the action illegal, Faubus removed the troops. When the students tried to enter again on September 24, they were taken into the school through a back door. Word of this spread throughout the community, and a thousand irate White citizens stormed the school grounds. The police desperately tried to keep the angry crowd under control as concerned onlookers whisked the students to safety.

Astonished Americans watched footage of brutish, White Southerners mercilessly harassing respectful African American children trying to get an education. Television began to sway public opinion and President Eisenhower was compelled to act. Eisenhower was not a strong proponent of civil rights. He feared that the Brown decision could lead to an impasse between the federal government and the states. However, Eisenhower did not believe the individual states had the right to contradict the Supreme Court. On September 25, he ordered the troops of the 101st Airborne Division into Little Rock and federalized the Arkansas National Guard in order to remove the soldiers from Faubus’s control. It was the first time federal troops were dispatched to the South since Reconstruction. For the next few months, the African American students attended school under armed supervision.

The following year, Little Rock officials closed the schools to prevent integration. But in 1959, the schools were open again. Both African American and White children were in attendance.

RUBY BRIDGES

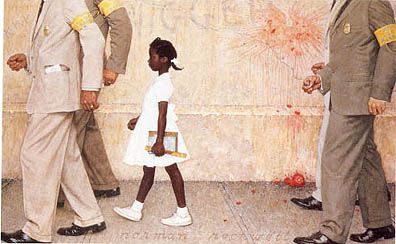

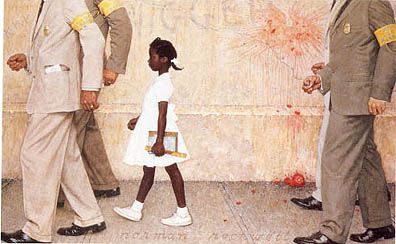

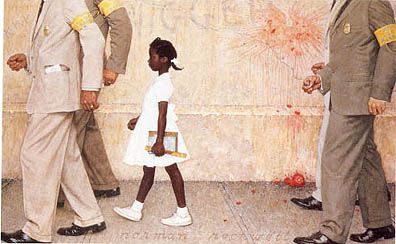

Yet another challenge was made by a little girl. Ruby Bridges attended a segregated kindergarten in 1959. In early 1960, Bridges was one of six African American children in New Orleans to pass the test that determined whether they could go to the all-White William Frantz Elementary School. In the end, only Bridges chose to attend and federal marshals escorted her to class to protect her. Primary Source: Painting

Primary Source: Painting

Norman Rockwell’s painting “The Problem We All Live With” captured the innocence of the African American students who integrated the schools of the South, as well as the swirling mix of hatred and the power struggle between White Southerners and the federal government.

Bridge’s story was commemorated by Norman Rockwell in the painting, The Problem We All Live With which was published in Look magazine on January 14, 1964. As Bridges describes it, “Driving up I could see the crowd, but living in New Orleans, I actually thought it was Mardi Gras. There was a large crowd of people outside of the school. They were throwing things and shouting, and that sort of goes on in New Orleans at Mardi Gras.” Former United States Deputy Marshal Charles Burks later recalled, “She showed a lot of courage. She never cried. She didn’t whimper. She just marched along like a little soldier, and we’re all very very proud of her.”

As soon as Bridges entered the school, White parents pulled their own children out. All the teachers except for one refused to teach while an African American child was enrolled. Only one person agreed to teach Ruby and that was Barbara Henry, from Boston, Massachusetts, and for over a year Henry taught her alone.

The Bridges family suffered for their decision to send her to William Frantz Elementary. Her father lost his job as a gas station attendant. The grocery store the family shopped at would no longer let them in. Her grandparents, who were sharecroppers in Mississippi, were evicted from their land.

Ruby Bridges has noted that many others in the community, both African American and White, showed support in a variety of ways. Some White families continued to send their children to Frantz despite the protests, a neighbor provided her father with a new job, and local people babysat, watched the house as protectors, and walked behind the federal marshals’ car on the trips to school.

Bridges, now Ruby Bridges Hall, still lives in New Orleans with her husband, Malcolm Hall, and their four sons. After graduating from a desegregated high school, she worked as a travel agent and later became a full-time parent. She is now chair of the Ruby Bridges Foundation, which she formed in 1999 to promote “the values of tolerance, respect, and appreciation of all differences”.

JAMES MEREDITH

In 1961, James Meredith applied to the University of Mississippi and insisted that it was his civil right to attend the state-funded university. Despite the Brown v. Board of Education ruling and the fact that the university was supported by all the taxpayers, it had yet to admit a single African American student.

In his application, Meredith wrote, “Nobody handpicked me… I believed, and believe now, that I have a Divine Responsibility… I am familiar with the probable difficulties involved in such a move as I am undertaking and I am fully prepared to pursue it all the way to a degree from the University of Mississippi.”

He was twice denied admission, and with the help of Medgar Evers of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Meredith studied the university, alleging that they had rejected him only because of his race, as he had a highly successful record of military service and academic courses. The case went through many hearings, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the Brown decision and supported Meredith’s right to be admitted.

The Governor of Mississippi, Ross Barnett, declared “no school will be integrated in Mississippi while I am your governor” and the state legislature passed a law that denied admission to any person “who has a crime of moral turpitude against him” or who had been convicted of any felony offense or not pardoned. The same day it became law, Meredith was accused and convicted of “false voter registration.”

President John F. Kennedy decided to step in and with the help of his younger brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy then ordered U.S. marshals and army troops to escort Meredith to school. When the marshals arrived with Meredith, a mob of angry Whites descended on the campus and a riot broke out. During the course of a day, over 100 federal troops and marshals were injured, and three civilians were killed. The so-called Battle of Oxford, ended the next day. The army and marshals never fired a shot.

Many students harassed Meredith during his time on campus. According to first-person accounts, students living in Meredith’s dorm bounced basketballs on the floor just above his room through all hours of the night. Other students ostracized him. When Meredith walked into the cafeteria for meals, the students eating would turn their backs. If Meredith sat at a table with White students, they would get up and go to another table. He persisted through the harassment and extreme isolation to graduate with a degree in political science. Primary Source: Photograph

Primary Source: Photograph

The political stand made by Alabama Governor George Wallace (on the left) at the schoolhouse door at the University of Alabama in 1963 is remembered as a seminal moment in the effort by White Southerners to preserve the segregated school system of the Jim Crow era.

THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA

The same year Meredith graduated, three African-American students became the first to integrate the University of Alabama. Vivian Malone Jones, Dave McGlathery and James Hood had all been rejected simply because of their race, but a federal district judge ordered that they be admitted.

Alabama’s Governor George Wallace had made a name for himself as a staunch segregationist, promising “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” When President Kennedy ordered the U.S. Marshals to escort the students to school, Wallace made a show of standing in the doorway to block their way. In response, Kennedy issued an executive order authorizing the federalization of the Alabama National Guard. Four hours later, General Henry Graham commanded Wallace to step aside, saying, “Sir, it is my sad duty to ask you to step aside under the orders of the President of the United States.” Wallace went on to give a speech promoting his racist ideas, but eventually moved, and the students were able to enroll. It was one of the most memorable standoffs in the struggle to integrate the schools and universities of the South.

CONCLUSION

The brave decision to put Jackie Robinson on the field, and Robinson’s decision to play on an all-White team, helped break down old barriers in sports. President Truman’s decision to integrate the armed forces ended hundreds of years of segregation. The individual decisions of students and their families to stand up against hatred and prejudice and go to school, a simple task most of us take for granted, was done at enormous physical risk. Death literally stalked them on their way to class. And the decisions by Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy to support the students instead of the White leaders who ran those schools, was brave as well. No politician wants to risk losing votes, and it would be foolish to apply modern ideas about what would be popular to a time when racial prejudice was proclaimed proudly and openly by millions of White Southerners.

Yet, without these individuals, the later work of Dr. King and the marches and protests that most Americans are familiar with, probably would not have happened. So, how did individuals advance the Civil Rights Movement?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: The Civil Rights Movement began slowly after WWII with the first big successes coming when the Supreme Court and then a few brave individuals ended school segregation.

African Americans have been working for their civil rights for generations. When slavery ended after the Civil War in 1865, three amendments to the Constitution were ratified that ended slavery, granted former slaves citizenship, and guaranteed voting rights to all men. However, a new system of laws was established in the South by White leaders who blocked these rights. African Americans lived as second-class citizens with no vote.

Segregation was a way of life in the South. African Americans could not eat in restaurants, go to movie theaters, or even drink from the same drinking fountains as Whites. Their children went to segregated schools and they rode in the back of city busses. This system was nicknamed Jim Crow.

In the early 1900s, African Americans had started working against this system, especially during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s.

Some progress was made in the 1940s after World War II. The first African Americans began playing for major league baseball teams. Also, President Truman desegregated the military and eliminated blacks-only units. However, when a young African American boy was murdered in the South, an all-White jury set his White killers free, and it was clear that segregation in the South would be hard to change.

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled that segregated schools were unconstitutional. This undid an older ruling. Despite their decision, most White leaders in the South refused to integrate their schools.

In Little Rock, Arkansas, nine African American students tried to enroll in high school. When mobs of Whites were going to attack them, President Eisenhower ordered the national guard to escort them to school.

Ruby Bridges became the first African American girl to attend her school when she enrolled in kindergarten. Federal marshals had to escort her to school so she would not be hurt by White mobs.

James Meredith became the first African American to attend the University of Mississippi. President Kennedy ordered the National Guard to escort him to school. For three days there was rioting as Whites tried to keep him out.

At the University of Alabama, the governor tried to stand in the doorway and prevent African Americans from enrolling.

VOCABULARY

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

Jackie Robinson: First African American baseball player to play for a major league team.

Emmitt Till: African American teenager from Chicago who was murdered by Whites in 1955 while visiting his family in Mississippi. His murder and open casket funeral brought national attention to the issue of Jim Crow segregation and racism in the South.

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP): Organization dedicated to promoting African American rights through the justice system. It was established in 1909 as part of the Niagara Movement.

Thurgood Marshall: NAACP lawyer who argued the Brown v. Board of Education case and was later appointed to be the first African American justice on the Supreme Court.

Earl Warren: Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in the 1950s and 1960s who pushed the Court to rule favorably on numerous cases related to civil rights.

Little Rock Nine: Group of African American students who integrated the main high school in Arkansas under the protection of the National Guard.

Ruby Bridges: African American girl who was the first to integrate Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans. She became the subject of Norman Rockwell’s painting “The Problem We All Life With.”

James Meredith: First African American student at the University of Mississippi.

George Wallace: Governor of Alabama during the 1960s who was a champion of segregation. His most famous line was “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

![]()

COURT CASES

Plessy v. Ferguson: 1896 Supreme Court case in which the court declared that racially segregated schools and other public facilities were constitutional establishing the “separate but equal” doctrine. It was overturned in the Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954.

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka: 1954 Supreme Court decision that ended segregated schools by overturning the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling.

![]()

EVENTS

Battle of Oxford: Rioting by White citizens and the efforts by US Marshals and army troops to keep the peace at the University of Mississippi when James Meredith became the first African American student to enroll there.

![]()

LAWS

Jim Crow: The nickname for a system of laws that enforced segregation. For example, African Americans had separate schools, rode in the backs of busses, could not drink from White drinking fountains, and could not eat in restaurants or stay in hotels, etc.

Executive Order 9981: Executive order issued by President Truman in 1948 ending racial segregation in the military.

Separate but Equal: Legal doctrine established by the Supreme Court in the Plessy v. Ferguson case that segregated schools and other public institutions were legal so long as they were equal.

Was it common for black students to be escorted to school by soldiers?

If a modern day version of little rock nine occurred, would the outcome be the same as it was in the 60s? How would people react today compared to those in the past?

Why did caucasians still hate african americans even after the civil war?

How did “Jim Crow” laws get its name?

Even though they mention trying to equally get white and african americans to attend school together, did it solve the poverty that african americans still currently go through today?

I’m curious to know what African American students’ perspectives were like knowing that they were continuously being monitored for the sake of integrated schooling.

How common was it that African American students were escorted by the military, other than the incident in Little Rock?

What did people in the North do about the problems going on in the South? Were the students supported by the North or maybe riots that were made against segregated schools?

Were there any examples of white students supporting or wanting to become friends with Bridges or Meredith in school?

Why did Barbara Henry continue to teach Ruby Bridges when no one else would?

Was George Wallace a liked governor/

Was Ruby Bridges ever harmed in any way?

Was Barbra Henry ever harassed by other White people for teaching Ruby Bridges?

What was life like in the North compared to the South for black children trying to attend white schools?

Hasn’t sports nowadays been categorized as this one particular race being good at that sport, while the other has no chance?

Was there a high rate of students studying/ graduating with a degree in political science? African Americans were usually very passionate about ending segregation so I would assume many would study about the topic of laws and such.

When James Meredith was enrolled, did segregation get in the way of his academics? Were teachers biased in having him fail?

If George Wallace didn’t move at all, what would have happened to him along with people who supported his standoff?

I was wondering the same thing actually, like would they have ever had a chance to graduate?

Do you think if the Emmit Till incident happened in this day an age that their would be way more attention around it? And a lot more people would riot?

I definitely would agree that there would be way more attention to the case of Emmit Till if it were to happen in this day and age. Especially with the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, I believe that there would be riots and people doing whatever it takes to fight for justice as they did for George Floyd.

During the Civil Rights Movement, were group efforts more effective or were individual people efforts more effective? In my opinion, it was likely a team effort because leaders likely led groups of people in order to become super effective. Although, wouldn’t technically the people be more effective because they are the ones suffering to get what they want?

Although it was displayed in the reading that Governor Orval Faubus’s intentions for mobilizing the Arkansas National Guard was “to prevent the Little Rock Nine from White mobs trying to violently stop them”, was his true intentions masked?–that he too, wanted to make sure the African American students did not get into Central High School?

How did the murder of Emmitt Till affect the culture of the south?

James Meredith was known as one of the first African Americans who attended college, after graduated from college, did he do anything to support the younger African American to go school and deal with assault while enrolling?

Although the Little Rock Nine attended school under armed supervision, how were their daily lives at school? How did the white students treat them as the school year went on? Did their guards really “protect” them from violence caused by other students?

I found this online resource that can provide more insight and information on the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case. It also provides some historical context to this case.

Link:https://www.history.com/news/brown-v-board-of-education-the-first-step-in-the-desegregation-of-americas-schools

Why did the Little Rock Nine agree to attend an all-white school with the risk of being harassed and assaulted? Was it due to all-white schools receiving better funding and privileges than all-black schools?

Why didn’t Congress force a more direct approach to the integration of schools? Rather knowing that Southern schools did not want to comply, why wasn’t an immediate force put on the integration of schools implemented?

In what ways has Ruby’s strength and courage affected our lives today?