INTRODUCTION

Organized labor has made things better for American workers. Today, many workers enjoy higher pay, better hours, and safer working conditions than they did 100 years ago. Today, many workers have insurance to help pay for medical care and several weeks’ vacation thanks to organized labor.

These changes were not easy to win. Jobs and lives were lost in the fight for better pay. The fight began during the Gilded Age, when workers started to come together to fight for change.

When the workers are united, industrialists have less power over their companies. After all, how can a captain of industry be successful if their workers are going on strikes? This power sharing can be hard, messy, and can sometimes end up hurting a business.

In a 100% socialist society, workers have all the control and there are no owners. Those who do the work get all the rewards. America has never tried a socialist system, and we know from the 20th century that this system has failed in other countries.

What do you think? Who should be in charge, workers or owners?

ORGANIZED LABOR

In the middle of the 1800s, a lot of American work was still done on farms. But by the beginning of the 1900s, the United States economy was based on factory work.

Most Americans living in the Gilded Age knew nothing of the life of millionaires such as Rockefeller, Carnegie and Morgan. They worked 10 hour shifts, 6 days a week, and earned barely enough money needed to survive. Even 8-year-old children worked instead of going to school. Men and women would work until their bodies could not anymore, which meant that they would lose their jobs and have no way to earn money. There was no medical insurance. Pregnant women would be fired and workers who got hurt on the job got fired instead of taken care of by the company owners.

Workers realized that they needed to come together and demand change. They didn’t have a lot of money, education, or political power. Even so, they knew there were more workers than there were owners, so they used that to their advantage.

Unions did not just appear overnight. In fact, it was very hard to start a union. Even though unions were legal, bosses usually tried to stop a union from forming. Sometimes fights between owners and workers even turned violent.

In the late-1800s, many Americans thought that a violent revolution was coming in America. How long would workers put up with being poor? Industrial titans, or bosses, including John Rockefeller built castles and fortresses to fight against the revolutions they thought were about to happen.

Unions grew, slowly but surely. As workers tried to form nationwide union organizations, they faced significant problems. The army was sometimes called to stop these unions and judges almost always sided with the bosses.

Another problem workers faced was that it was often hard to agree on common goals. Some believed in Marxism and wanted to get rid of all the owners, while others just wanted a few cents more per hour. Workers also fought about whether or not women and African Americans should be able to join their unions.

THE GREAT UPHEAVAL

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877 started with a 10% pay cut. Railroad workers in Martinsburg, West Virginia decided they had had enough when the owners of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad company made a new 10% pay cut, just 8 months after cutting their pay already. On July 16, 1877, workers in Martinsburg drove all the trains back into the roundhouse and said that no trains would leave until the owners restored their pay. The local townspeople got together at the railyard to show their support for the strikers.

Strikes or other actions seen as disturbances are usually dealt with at the local level. The mayor of Martinsburg tried to threaten the workers on strike, but they just laughed and booed. The workers also outnumbered the local police, so they couldn’t do much to stop the workers. The mayor then decided to turn to the governor of West Virginia for help who sent soldiers from the National Guard to Martinsburg to try to force the workers to run the trains. However, most of the members of the National Guard were railroad workers too. After two people were killed in the fight between the workers and the guardsmen, the guards decided to put down their guns and help the workers.

The trains left the station only when President Hayes sent soldiers from the army to force the railroad men back to work. Even then, the trains were sabotaged. Only one train reached its final destination. Primary Source: Print

Primary Source: Print

An artist’s depiction of the destruction of the railroad depot at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia during the Great Upheaval.

The Martinsburg Strike might have gone down in history as one of many small local strikes put down by force. But as news of what happened spread, railroad men across the country joined the Martinsburg Strike.

The police, the National Guard, and the United States Army fight with angry mobs across America. Rich people feared that the worst had finally come. A violent revolution seemed to be spreading through the country.

But then it stopped. In some cases, the strikes were stopped by force. In others, the strikers just gave up. After all, most workers were not trying to overthrow the government or the social order. They just wanted higher pay and more time to spend with their families. The Great Upheaval was not the first strike in American history but was the first strike to involve so many different workers in so many different places.

What did this mean for America? It looked like the mass strike had failed, but in many places, the time workers did get what they wanted. And probably there were times when owners didn’t cut their workers’ pay because they were afraid of what might happen.

The Great Upheaval happened suddenly and wasn’t planned. But it happened because many workers cared about the same things. More than 100,000 workers had gone on strike, shutting down about half of the country’s rail system.

When the strike ended, over 100 people had been killed and a thousand more were in jail, and rail lines, cars, and roundhouses had been damaged. The Great Upheaval was over, but America had not seen the last of the mass strike.

LABOR VS. MANAGEMENT

The battle lines were clearly drawn. People were either workers or bosses, and both sides disliked the other. The number of Americans who ran their own shops instead of working for someone else began to go down during the Gilded Age, and workers began to feel powerful as their numbers grew. They started to demand more and more from their bosses. When those owners said no, the workers worked to find ways to win what they wanted.

Those who run factories came up with plans to stop the workers from uniting. At times the relationship between the group was tense. Other times it was ugly like a schoolyard fight.

The workers’ favorite way to make change was the strike. A strike works because workers refuse to work, and the company can’t make or sell anything. At some point the owners don’t want to lose any more money so they agree to what the workers want. Strikes were not new, but they started getting popular during the Gilded Age.

Even though workers often used strikes in the 1800s, they were not often successful. Sometimes this was because of bad planning and sometimes because people in government supported business owners. So, unions tried to think of other ways to get what they wanted. One other option was the boycott. For example, if the workers at a shoe factory could get enough support from the local townspeople, a boycott could bring good results. The union would talk to the town about their situation hoping that no one would buy any shoes from the factory until the business owners agreed to a pay raise. Boycotts could be successful in a small town where the factory mostly sold to people in just that town.

When it looked like nothing would make a difference, workers sometimes also used illegal methods. For example, sabotage of factory equipment was not unknown. Sometimes, the foreman or the owner might even be attacked.

Business owners had tricks of their own. If a company had a high inventory of products to sell, the boss might be able to start a lockout, which is the opposite of a strike. In this case, the owner tells the employees not to show up until they agree to have their pay cut. Sometimes when a new worker was hired the employee was told to sign a yellow-dog contract, or a promise not to join a union.

Strikes could be stopped in different ways. The first way was to hire strikebreakers, or scabs, to replace the regular workers. Here things often turned violent. The crowded cities always had someone who needed a job and would be willing to cross the picket line of striking workers. The striking workers would, of course, be angry and there were often fights between scabs and strikers.

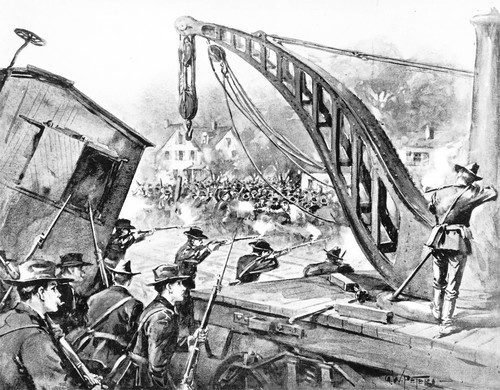

Before the 1900s, the government never sided with the union in a labor debate. Bosses got the courts to issue injunctions saying that the strikes were illegal. If the strike continued, the workers who joined in would be thrown in jail. If these efforts failed to stop the strike, government leaders at all levels would send in the police or army, such as what happened during the Great Upheaval. Primary Source: Drawing

Primary Source: Drawing

An artist’s rendition of the arrival of the National Guard to break the Homestead Strike.

What was at stake? Each side felt they were fighting for their life. The owners felt if they could not have cheap costs to beat their competition, they would have to close the factory. They said they could not possibly give the workers what they wanted.

What did the workers want? In the whole history of labor strife, workers mostly wanted two things: higher pay and better working conditions.

EARLY NATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS

One reason that owners often beat the workers in labor disputes was that workers did not all have the same goals. By favoring one group over another, the bosses could get workers to fight amongst themselves. If a union could get workers to join together from many towns, they might be able to start a more successful boycott or strike, but having different groups work together across a large area was very difficult.

Owners created and shared blacklists with each other. These lists had the names of any workers in the union. If anyone on the list showed up in another town trying to get hired (or to start another union), the owners would not give them the job. Still, national organizations were bound to start up eventually. The first group to overcome all the challenges was the National Labor Union.

By 1866, there were about 200,000 workers in local unions across the United States. William Sylvis started the first nationwide labor organization, named the National Labor Union. Sylvis had big dreams. Not only did the NLU fight for higher pay and shorter hours, Sylvis wanted workers to get involved in politics. The NLU supported laws to stop prison labor and laws to raise farm prices.

The National Labor Union brought together skilled and unskilled workers, as well as farmers. They did not include African Americans, however. Even though they needed as many workers as possible, racist feelings were strong. In the end, the NLU tried to represent too many different groups who each wanted different things. The farmers had their own goals. Skilled and unskilled workers had different lives and values as well. The NLU fell apart in the 1870s.

THE KNIGHTS OF LABOR

Soon, the Knights of Labor were leaders of organized labor. The Knights started in 1869 by Uriah Stephens. They were open to all workers, including women and African Americans. The Knights thought that class was more important than race or gender and that if they were going to change laws all workers needed to join together.

The Knights supported the political plans of the NLU and more. They wanted to put limits on immigration, pass laws to stop child labor, and they wanted the government to take over the railroads, telegraphs, and telephones. By 1886, the Knights had 750,000 workers as members. Then everything went wrong.

On May 1, 1886, International Workers Day, the Knights went on strike. They were asking for an eight-hour day for all workers. At a rally in Haymarket Square in Chicago on May 4, someone threw a bomb into the crowd. One police officer died, and several people were hurt.

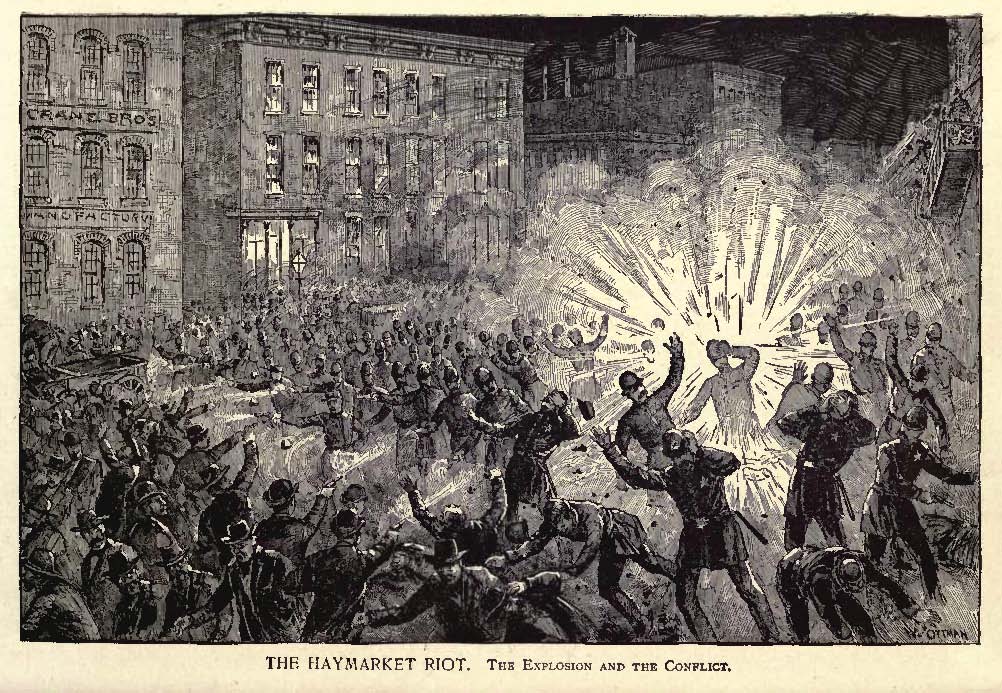

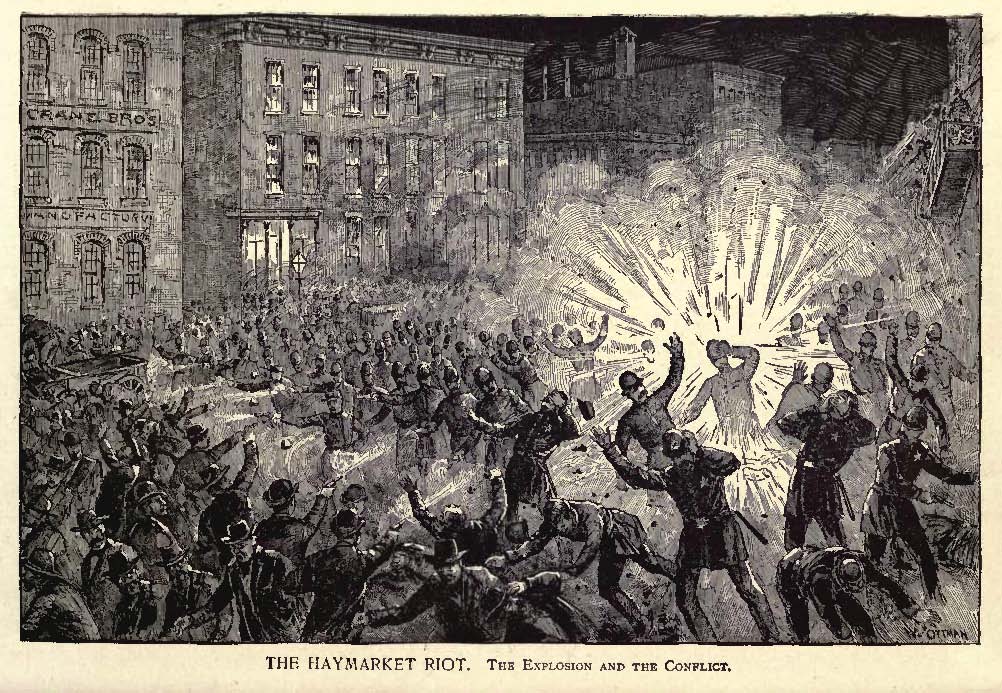

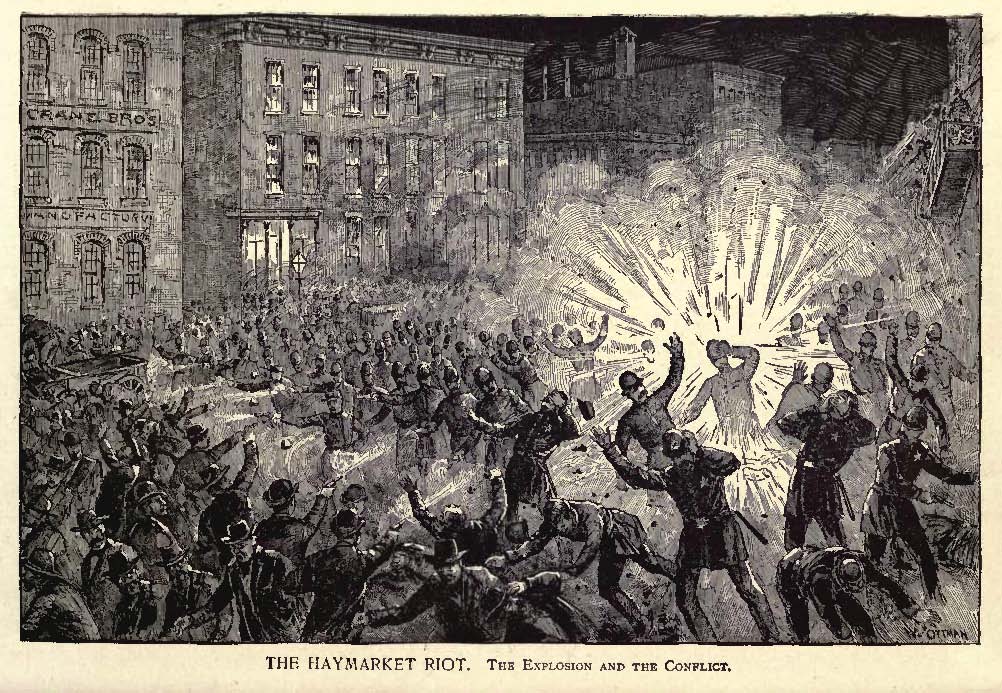

We will never know who threw the bomb, but newspapers, government, and Americans in general blamed the Knights of Labor. Leader Terence Powderly gave a speech saying that the Knights did not support the bombing. But Americans started to think that labor unions were connected with anarchists and violence. Soon after, many of the Knights members started to quit. The Knights of Labor disappeared after the Haymarket Square bombing, but labor leaders learned important lessons that would help the next organization of workers succeed. Primary Source: Drawing

Primary Source: Drawing

An artist’s rendition of the explosion at Haymarket Square in Chicago, Illinois on May 4, 1886. One police officer was killed. The violence turned many Americans against the labor movement and limited support for the Knights of Labor.

AMERICAN FEDERATION OF LABOR

Labor leader Samuel Gompers had a motto: Keep it simple. He thought that America’s basic system of capitalism was good and saw no need to get rid of all owners or change the government. What Gompers learned that helped him be successful was that workers cared the most about personal issues. They wanted higher pay and better working conditions. These problems are often called bread and butter issues because they are so basic and always bring working people together. By keeping it simple, Gompers knew that unions could avoid the same problems that caused the National Labor Union and the Knights of Labor to fall.

In December of 1886, the same year the Knights of Labor had its terrible day at Haymarket Square, Gompers met with the leaders of other craft unions to form the American Federation of Labor. The AFL was a loose grouping of smaller craft unions, made up of workers who had some special knowledge. These included the masons’ union, the hat makers’ union or Gompers’s own cigar makers’ union. Every member of the AFL was therefore a skilled worker.

Gompers had no dream of bringing every possible worker into the AFL. Tradespeople were needed and already earned more money than unskilled factory workers. Gompers knew that the AFL would have more power if unskilled workers were not included. He served as president of the union every year except one until his death in 1924.

Even though Gompers was careful, he was not afraid to call for a strike or a boycott. The whole AFL did sometimes take such action and provided help for members when the union went on strike. Because he was cautious, stuck to bread and butter issues, and did not try to use his union to promote progressive political ideas, Gompers kept the support of the American government and most people. By 1900, the AFL had grown to over 500,000 tradespeople. Gompers was seen as the unofficial leader of workers in America.

Keeping it simple worked. Although the bosses still had the upper hand with the government, unions were growing in size and importance. There were over 20,000 strikes in America in the last two years of the 1800s. Workers lost about half, but in many cases, owners gave them at least some of what they wanted. The AFL was the most well-known national labor organization up until the 1930. Smart leadership, patience, and realistic goals made life better for the hundreds of thousands of working Americans it served. Primary Source: Drawing

Primary Source: Drawing

An artist’s rendition of the violent clash between the National Guard and striking Pullman Car Company workers.

EUGENE V. DEBS AND AMERICAN SOCIALISM

The American Federation of Labor had shown the bread and butter issues were more popular than calling for a total change in the government, but American radicalism was not dead. The number of those who felt the American capitalist system was broken was in fact growing fast.

American socialists liked the ideas of Karl Marx, the German philosopher. Many asked why so many working Americans should have so little while a few owners grew so rich. No wealth could exist without the hard work of the workers. They said that the government should own all the businesses and divide the money among those who actually created the products. While the current owners would lose, many workers would benefit from the change. More and more radicals began to appear as industries spread, but they also had a lot of enemies.

The man who led the Socialists in America was Eugene Debs. Born in Indiana in 1855 to a family of French immigrants, Debs started working in the railroad industry, and formed the American Railway Union in 1892.

Two years later, he led one of the largest strikes in American history, the great Pullman Strike. When its workers refused to accept a pay cut, The Pullman Car Company fired 5,000 employees. To show support, Debs called for the members of the American Railway Union to stop any trains that used Pullman cars. When a court said that the strike was illegal things got ugly. President Cleveland ordered the army to stop the strikers and Debs was arrested. Things calmed down and the strike failed. Primary Source: Campaign Poster

Primary Source: Campaign Poster

1904 poster celebrating Socialist Party candidate Eugene Debs.

After the Pullman Strike and being in jail for six-month, Debs decided that it was time for a big change in America, and that the government was the place to make that change. In 1900 he ran for President as a socialist and got 87,000 votes.

Other people who had the same ideas joined with him to form the Socialist Party the following year. At its strongest, the party had over 100,000 members. Debs ran for President four more times. In the election of 1912, he received over 900,000 votes. After being arrested for anti-war activities during World War I, he ran for President from jail and got 919,000 votes. Debs died in 1926. He never won an election, but over 1,000 Socialist Party members were elected to state and city governments.

THE WOBBLIES

The members of the Industrial Workers of the World were even more radical than the Socialists. This union thought that there would never be any way of working with owners. Founded in 1905, and led by William “Big Bill” Haywood, the Wobblies as they were called, encouraged their members to fight for justice directly against the owners. Although small in number, they led hundreds of strikes across America, calling for an end to America’s capitalist system. The IWW didn’t get what they wanted, but they sent a strong message across America that workers were being mistreated.

When the United States entered World War I, the Wobblies argued that the war was wrong. Many were arrested, attacked or killed. Membership went after the war, but for 20 years the IWW was on the cutting edge of radical American activism. Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

Primary Source: Editorial Cartoon

A cartoon critical of the IWW as destroyers of America.

THEODORE ROOSEVELT

Workers rarely got help from the White House. President Hayes ordered the army to break the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. President Cleveland ordered the army to stop the Pullman Strike of 1894. Governors and mayors used the National Guard and police to confront workers on strike.

When Pennsylvania coal miners went on strike in 1902, there was no reason to believe anything had changed. But this time things were different. Teddy Roosevelt was in the White House.

John Mitchell, president of the United Mine Workers, was the leader of the miners. He was soft-spoken yet determined. Many compared him to Abraham Lincoln. In the spring of 1902, Mitchell asked the coal operators for better pay, shorter hours, and to recognize the union as the representative of their workers. The owners, led by George Baer, said no. On May 12, 1902, 140,000 miners walked off the job, and the strike was on.

Mitchell worked hard to negotiate with Baer, but Baer did not want to cooperate. Even leaders such Mark Hanna and J.P. Morgan tried on the owners to open talks with the union, but even this didn’t work. As the weeks passed, the workers started getting upset. While on strike they weren’t getting paid which was frustrating, and frustration turned into violence.

As summer turned into fall, President Roosevelt wondered what the angry workers and regular people without coal to head their homes would do if the strike lasted into the cold days of winter. He decided to try to help end the strike.

No President had ever tried to negotiate a deal to end a strike before. Roosevelt asked Mitchell and Baer to come to the White House on October 3 to work out a compromise. Mitchell said the miners would agree to arbitration. In arbitration, all sides tell what they want to an outside person, the arbitrator, and then agree to go along with the arbitrator’s choice. Baer said the President was treating him like a “common criminal,” and said he would never make any deals.

Roosevelt was worried that the fighting would get worse and could end with a war between the rich and poor. After the miners left the White House, he promised to end the strike. He was impressed by Mitchell, who was polite and respectful, but couldn’t stand Baer. Roosevelt said that if he weren’t president, he would have thrown Baer out of a White House window.

He called Secretary of War Elihu Root and ordered him to get the army ready. This time, however, the army would not be used against the strikers. The mine owners were told that if no deal were reached to end the strike, the army would take over the mines and make sure people would be able to have coal to heat their homes in the winter. Roosevelt did not seem to mind that the Constitution did not give him the power to do this!

J.P. Morgan finally got Baer and the other owners to let an arbitrator decide how to end the strike. The miners were awarded a 10 percent pay raise, and their workday was cut to eight or nine hours. In exchange, the owners were not forced to recognize the United Mine Workers.

Workers across America cheered Roosevelt for standing up to the mine owners. It definitely seemed like the White House would help the labor movement.

CONCLUSION

Owners got their way at the start of the Gilded Age, but as they grew in number, workers began to form unions and fought for more control over their pay and working conditions. In the beginning, the government usually supported the owners, but by the 1900s, politicians viewed themselves as arbitrators, trying to help the two sides come to an agreement.

There were other options. Men like Eugene Debs wanted to get rid of all owners and give all the money to the workers. These socialists never won enough support to put their ideas into practice in America, but they offered a different choice.

What do you think? Who should be in charge, workers or owners?

CONTINUE READING

SUMMARY

BIG IDEA: Organized labor unions emerged in the late 1800s, although their efforts were often limited because government generally sided with business owners.

The period after the Civil War saw a growth of labor unions. The Great Upheaval of 1877 was the nation’s first mass strike as workers in the railroad industry started a strike that spread and was supported by striking workers across the nation.

Labor unions used boycotts and strikes to stop work and try to force owners to meet their demands. Owners locked out workers and hired scabs to break strikes. Most strikes in the late 1800s went badly for workers. A large number of immigrants were willing to work for low wages and take the place of striking workers. Government usually supported owners and the police and army broke strikes at Carnegie’s steel plant in Pittsburg and a strike at the Pullman railroad car factory in Chicago.

The first major union was the Knights of Labor. They lost support after the Haymarket Square Riot.

A new union grew as the Knights of Labor fell out of favor. The American Federation of Labor was led by Samuel Gompers and focused on basic issues like wages and working conditions instead of political reform. The AFL was a composite of many smaller craft unions, so they did not represent unskilled workers.

Eugene Debs led the American Socialist Party. This group wanted to change America’s system of government. They wanted to take leadership of the nation’s industries away for the rich. Although they were popular with workers, they never gained the support of more than a small percentage of all Americans.

A more extreme group were the Industrial Workers of the World. They wanted a violent revolution to take power away from the wealthy and the overthrow the government. Although Americans rejected these ideas, they eventually caught on in Russia and led to the Communist Revolution there in 1917.

VOCABULARY

KEY CONCEPTS

Union: An organization of workers. They work together to negotiate for better pay, hours, working conditions, etc. Sometimes they organize strikes or other forms of protest.

Mass Strike: A strike in which the workers in many locations stop work at the same time. One example was the Great Upheaval in 1877 when nearly all railroad operations in America stopped.

Boycott: When workers convince consumers to not purchase goods from a particular business. If it succeeds, the business owners capitulate to the workers’ demands because of the fear of lost revenue.

Sabotage: Purposeful destruction of property as a form of protest.

Lockout: When owners close the doors to their business and refuse to let workers in. It is a way of limiting the power of unions.

Yellow-Dog Contract: An agreement a worker must sign when starting a job agreeing not to join a union.

Scab: A replacement worker hired during a strike.

Picket Line: The line made up of striking workers outside a business. Workers usually carry signs, chant, and try to prevent scabs from entering to take their jobs.

Blacklist: A list of union leaders passed around among business owners. These men and women would not be hired because they might cause problems for the owners.

Bread and Butter Issues: Nickname for the basic concerns of works such as better pay, fewer working hours, and safety. In contrast to larger concerns such as racial or gender equality.

Socialist: A follower of Karl Marx. They believed that workers should share the financial rewards of their labor and companies should be owned collectively.

Arbitration: A way of solving disputes in which both sides agree to abide by the decision of an outside, non-biased party.

![]()

PEOPLE AND GROUPS

National Labor Union: Early national union formed in 1866. It failed because the organizers tried to include too many different workers who did not always agree on objectives or strategy.

Knights of Labor: Early successful union formed by Uriah Stephens. They admitted all wage earners including African Americans and women. They grew in popularity but weakened after the Haymarket Square incident in 1886.

Samuel Gompers: Founder of the American Federation of Labor

American Federation of Labor: Labor union founded by Samuel Gompers in 1886. It was formed by joining smaller unions of skilled workers.

Eugene Debs: Socialist union leader. He led the Pullman strike and ran unsuccessfully for president as a Socialist Party candidate.

Socialist Party: Small political party in America that was popular for a short time in the late 1800s. Eugene Debs led the party and ran for president as its candidate.

Industrial Workers of the World: Socialist political party led by Big Bill Haywood. Nicknamed the Wobblies, they advocated violent overthrow of the government and capitalist system.

William “Big Bill” Haywood: Founder and leader of the International Workers of the World.

![]()

EVENTS

Great Upheaval: Mass strike in 1877 that started in West Virginia but spread as many railroad workers went on strike.

Haymarket Square Incident: Sometimes called a riot, it was a labor rally in Chicago in 1886 in which a bomb exploded killing a police officer and injuring many others. Labor leaders were blamed for the violence and it led to reduced public support for unions, and especially for the Knights of Labor.

Pullman Strike: Strike by workers at the Pullman Car Company (which built railway cars) in 1894. It turned violent and failed when the government ordered federal troops to end the strike.